Lucy jamaica kincaid free download - simply

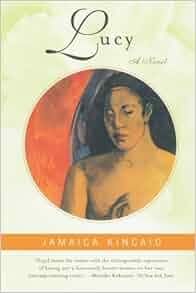

LUCY. Jamaica Kincaid. Farrar Straus Giroux. New York

Transcription

1 Jamaica Kincaid Farrar Straus Giroux New York

2 HI A R I A H ONE MORNING IN EARLY MARCH, Mariah said to me, You have never seen spring, have you? And she did not have to await an answer, for she already knew. She said the word spring as if spring were a close friend, a friend who had dared to go away for a long time and soon would reappear for their passionate reunion. She said, Have you ever seen daffodils pushing their way up out of the ground? And when they re in bloom and all massed together, a breeze comes along and makes them do a curtsy to the lawn stretching out in front of them. Have you ever seen that? When I see that, I feel so glad to be alive. And I thought. So Mariah is made to feel alive by some flowers bending in the breeze. How does a person get to be that way? I remembered an old poem I had been made

3 to memorize when I was ten years old and a pupil at Queen Victoria Girls School. I had been made to memorize it, verse after verse, and then had recited the whole poem to an auditorium full of parents, teachers, and my fellow pupils. After I was done, everybody stood up and applauded with an enthusiasm that surprised me, and later they told me how nicely I had pronounced every word, how I had placed just the right amount of special emphasis in places where that was needed, and how proud the poet, now long dead, would have been to hear his words ringing out of my mouth. I was then at the height of my two-facedness: that is, outside I seemed one way, inside I was another; outside false, inside true. And so I made pleasant little noises that showed both modesty and appreciation, but inside I was making a vow to erase from my mind, line by line, every word of that poem. The night after I had recited the poem, I dreamt, continuously it seemed, that I was being chased down a narrow cobbled street by bunches and bunches of those same daffodils that I had vowed to forget, and when finally I fell down from exhaustion they all piled on top of me, until I was buried deep underneath them and was never seen again. I had forgotten all of this until Mariah mentioned daffodils, and now I told it to her with (19) such an amount of anger I surprised both of us. We were standing quite close to each other, but as soon as I had finished speaking, without a second of deliberation we both stepped back. It was only one step that was made, but to me it felt as if something that I had not been aware of had been checked. Mariah reached out to me and, rubbing her hand against my cheek, said, What a history you have. I thought there was a little bit of envy in her voice, and so I said. You are welcome to it if you like. After that, each day, Mariah began by saying, As soon as spring comes, and so many plans would follow that I could not see how one little spring could contain them. She said we would leave the city and go to the house on one of the Great Lakes, the house where she spent her summers when she was a girl. We would visit some great gardens. We would visit the zoo a nice thing to do in springtime; the children would love that. We would have a picnic in the park as soon as the first unexpected and unusually warm day arrived. An early-evening walk in the spring air that was something she really wanted to do with me, to show me the magic of a spring sky. On the very day it turned spring, a big snowstorm came, and more snow fell on that day than

4 had fallen all winter. Mariah looked at me and shrugged her shoulders. How typical, she said, giving the impression that she had just experienced a personal betrayal. I laughed at her, but I was really wondering. How do you get to be a person who is made miserable because the weather changed its mind, because the weather doesn t live up to your expectations? How do you get to be that way? While the weather sorted itself out in various degrees of coldness, I walked around with letters from my family and friends scorching my breasts. I had placed these letters inside my brassiere, and carried them around with me wherever I went. It was not from feelings of love and longing that I did this; quite the contrary. It was from a feeling of hatred. There was nothing so strange about this, for isn't it so that love and hate exist side by side? Each letter was a letter from someone I had loved at one time without reservation. Not too long before, out of politeness, I had written my mother a very nice letter, I thought, telling her about the first ride I had taken in an underground train. She wrote back to me, and after I read her letter, I was afraid to even put my face outside the door. The letter was filled with detail after detail of horrible and vicious things (21) she had read or heard about that had taken place on those very same underground trains on which I traveled. Only the other day, she wrote, she had read of an immigrant girl, someone my age exactly, who had had her throat cut while she was a passenger on perhaps the very same train I was riding. But, of course, I had already known real fear. I had known a girl, a schoolmate of mine, whose father had dealings with the Devil. Once, out of curiosity, she had gone into a room where her father did his business, and she had looked into things that she should not have, and she became possessed. She took sick, and we, my other schoolmates and I, used to stand in the street outside her house on our way home from school and hear her being beaten by what possessed her, and hear her as she cried out from the beatings. Eventually she had to cross the sea, where the Devil couldn t follow her, because the Devil cannot walk over water. I thought of this as I felt the sharp corners of the letters cutting into the skin over my heart. I thought. On the one hand there was a girl being beaten by a man she could not see; on the other there was a girl getting her throat cut by a man she could see. In this great big world, why should my life be reduced to these two possibilities?

5 When the snow fell, it came down in thick, heavy glops, and hung on the trees like decorations ordered for a special occasion a celebration no one had heard of, for everybody complained. In all the months that I had lived in this place, snowstorms had come and gone and I had never paid any attention, except to feel that snow was an annoyance when I had to make my way through the mounds of it that lay on the sidewalk. My parents used to go every Christmas Eve to a film that had Bing Crosby standing waist-deep in snow and singing a song at the top of his voice. My mother once told me that seeing this film was among the first things they did when they were getting to know each other, and at the time she told me this I felt strongly how much I no longer liked even the way she spoke; and so I said, barely concealing my scorn, What a religious experience that must have been. I walked away quickly, for my thirteen-year-old heart couldn t bear to see her face when I had caused her pain, but I couldn t stop myself. In any case, this time when the snow fell, even I could see that there was something to it it had a certain kind of beauty; not a beauty you would wish for every day of your life, but a beauty you could appreciate if you had an excess of beauty to begin (23) with. The days were longer now, the sun set later, the evening sky seemed lower than usual, and the snow was the color and texture of a half-cooked egg white, making the world seem soft and lovely and unexpectedly, to me nourishing. That the world I was in could be soft, lovely, and nourishing was more than I could bear, and so 1 stood there and wept, for I didn t want to love one more thing in my life, didn t want one more thing that could make my heart break into a million little pieces at my feet. But all the same, there it was, and I could not do much about it; for even I could see that I was too young for real bitterness, real regret, real hard-heartedness. The snow came and went more quickly than usual. Mariah said that the way the snow vanished, as if some hungry being were invisibly swallowing it up, was quite normal for that time of year. Everything that had seemed so brittle in the cold of winter sidewalks, buildings, trees, the people themselves seemed to slacken and sag a bit at the seams. 1 could now look back at the winter. It was my past, so to speak, my first real past a past that was my own and over which I had the final word. I had just lived through a bleak and cold time, and it is not to the weather outside that 1 refer. I had lived

6 through this time, and as the weather changed from cold to warm it did not bring me along with it. Something settled inside me, something heavy and hard. It stayed there, and I could not think of one thing to make it go away. I thought. So this must be living, this must be the beginning of the time people later refer to as years ago, when I was young. My mother had a friendship with a woman a friendship she did not advertise, for this woman had spent time in jail. Her name was Sylvie; she had a scar on her right cheek, a human-teeth bite. It was as if her cheek were a half-ripe fruit and someone had bitten into it, meaning to eat it, but then realized it wasn t ripe enough. She had gotten into a big quarrel with another woman over this: which of the two of them a man they both loved should live with. Apparently Sylvie said something that was unforgivable, and the other woman flew into an even deeper rage and grabbed Sylvie in an embrace, only it was not an embrace of love but an embrace of hatred, and she left Sylvie with the marked cheek. Both women were sent to jail for public misconduct, and going to jail was something that for the rest of their lives no one would let them forget. It was because of this that I was not allowed (25) to speak to Sylvie, that she was not allowed to visit us when my father was at home, and that my mother s friendship with her was supposed to be a secret. I used to observe Sylvie, and I noticed that whenever she stopped to speak, even in the briefest conversation, immediately her hand would go up to her face and caress her little rosette (before I knew what it was, I was sure that the mark on her face was a rose she had put there on purpose because she loved the beauty of roses so much she wanted to wear one on her face), and it was as if the mark on her face bound her to something much deeper than its reality, something that she could not put into words. One day, outside my mother s presence, she admired the way my corkscrew plaits fell around my neck, and then she said something that I did not hear, for she began by saying, Years ago when I was young, and she pinched up her scarred cheek with her fingers and twisted it until I thought it would fall off like a dark, purple plum in the middle of her pink palm, and her voice became heavy and hard, even though she was laughing all the time she spoke. That is how I came to think that heavy and hard was the beginning of living, real living; and though I might not end up with a mark on my cheek, I had no doubt that I would end up with a mark somewhere.

7 I was standing in front of the kitchen sink one day, my thoughts centered, naturally, on myself, when Mariah came in danced in, actually singing an old song, a song that was popular when her mother was a young woman, a song she herself most certainly would have disliked when she was a young woman and so she now sang it with an exaggerated tremor in her voice to show how ridiculous she still found it. She twirled herself wildly around the room and came to a sharp stop without knocking over anything, even though many things were in her path. She said, I have always wanted four children, four girl children. I love my children. She said this clearly and sincerely. She said this without doubt on the one hand or confidence on the other. Mariah was beyond doubt or confidence. I thought. Things must have always gone her way, and not just for her but for everybody she has ever known from eternity; she has never had to doubt, and so she has never had to grow confident; the right thing always happens to her; the thing she wants to happen happens. Again I thought. How does a person get to be that way? Mariah said to me, I love you. And again she said it clearly and sincerely, without confidence or (27) doubt. I believed her, for if anyone could love a young woman who had come from halfway around the world to help her take care of her children, it was Mariah. She looked so beautiful standing there in the middle of the kitchen. The yellow light from the sun came in through a window and fell on the pale-yellow linoleum tiles of the floor, and on the walls of the kitchen, which were painted yet another shade of pale yellow, and Mariah, with her pale- yellow skin and yellow hair, stood still in this almost celestial light, and she looked blessed, no blemish or mark of any kind on her cheek or anywhere else, as if she had never quarreled with anyone over a man or over anything, would never have to quarrel at all, had never done anything wrong and had never been to jail, had never had to leave anywhere for any reason other than a feeling that had come over her. She had washed her hair that morning and from where I stood I could smell the residue of the perfume from the shampoo in her hair. Then underneath that I could smell Mariah herself. The smell of Mariah was pleasant. Just that pleasant. And I thought. But that s the trouble with Mariah she smells pleasant. By then I already knew that I wanted to have a powerful odor and would not care if it gave offense.

8 On a day on which it was clear that there was no turning back as far as the weather was concerned, that the winter season was over and its return would be a noteworthy event, Mariah said that we should prepare to go and spend some time at the house on the shore of one of the Great Lakes. Lewis would not aecompany us. Lewis would stay in town and take advantage of our absenee, doing things that she and the ehildren would not enjoy doing with him. What these things were I could not imagine. Mariah said we would take a train, for she wanted me to experience spending the night on a train and waking up to breakfast on the train as it moved through freshly plowed fields. She made so many arrangements I had not known that just leaving your house for a short time could be so complieated. Early that afternoon, because the children, my charges, would not return home from school until three, Mariah took me to a garden, a place she described as among her favorites in the world. She covered my eyes with a handkerchief, and then, holding me by the hand, she walked me to a spot in a clearing. Then she removed the handkerchief and said, Now, look at this. I looked. It was a big (29) area with lots of thick-trunked, tall trees along winding paths. Along the paths and underneath the trees were many, many yellow flowers the size and shape of play teacups, or fairy skirts. They looked like something to eat and something to wear at the same time; they looked beautiful; they looked simple, as if made to erase a complicated and unnecessary idea. I did not know what these flowers were, and so it was a mystery to me why I wanted to kill them. Just like that. I wanted to kill them. I wished that I had an enormous scythe; I would just walk down the path, dragging it alongside me, and I would cut these flowers down at the place where they emerged from the ground. Mariah said, These are daffodils. I m sorry about the poem, but I m hoping you ll find them lovely all the same. There was such joy in her voiee as she said this, sueh a music, how could I explain to her the feeling I had about daffodils that it wasn t exactly daffodils, but that they would do as well as anything else? Where should I start? Over here or over there? Anywhere would be good enough, but my heart and my thoughts were racing so that every time I tried to talk I stammered and by accident bit my own tongue. Mariah, mistaking what was happening to me

9 for joy at seeing daffodils for the first time, reached out to hug me, but I moved away, and in doing that I seemed to get my voice back. I said, Mariah, do you realize that at ten years of age I had to learn by heart a long poem about some flowers I would not see in real life until I was nineteen? As soon as I said this, I felt sorry that I had cast her beloved daffodils in a scene she had never considered, a scene of conquered and conquests; a scene of brutes masquerading as angels and angels portrayed as brutes. This woman who hardly knew me loved me, and she wanted me to love this thing a grove brimming over with daffodils in bloom that she loved also. Her eyes sank back in her head as if they were protecting themselves, as if they were taking a rest after some unexpected hard work. It wasn t her fault. It wasn t my fault. But nothing could change the fact that where she saw beautiful flowers I saw sorrow and bitterness. The same thing could cause us to shed tears, but those tears would not taste the same. We walked home in silence. I was glad to have at last seen what a wretched daffodil looked like. When the day came for us to depart to the house on the Great Lake, I was sure that I did not want (31) to go, but at midmorning I received a letter from my mother bringing me up to date on things she thought I would have missed since I left home and would certainly like to know about. It still has not rained since you left, she wrote. How fascinating, I said to myself with bitterness. It had not rained once for over a year before I left. I did not care about that any longer. The object of my life now was to put as much distance between myself and the events mentioned in her letter as I could manage. For I felt that if I could put enough miles between me and the place from which that letter came, and if I could put enough events between me and the events mentioned in the letter, would I not be free to take everything just as it came and not see hundreds of years in every gesture, every word spoken, every face? On the train, we settled ourselves and the children into our compartments two children with Mariah, two children with me. In one of the few films I had seen in my life so far, some people on a train did this settled into their compartments. And so I suppose I should have felt excitement at doing something I had never done before and had only seen done in a film. But almost everything I did now was something I had never done before, and so the new was no longer thrilling to me unless

10 it reminded me of the past. We went to the dining car to eat our dinner. We sat at tables the children by themselves. They had demanded that, and had said to Mariah that they would behave, even though it was well known that they always did. The other people sitting down to eat dinner all looked like Mariah s relatives; the people waiting on them all looked like mine. The people who looked like my relatives were all older men and very dignified, as if they were just emerging from a church after Sunday service. On closer observation, they were not at all like my relatives; they only looked like them. My relatives always gave backchat. Mariah did not seem to notice what she had in common with the other diners, or what I had in common with the waiters. She acted in her usual way, which was that the world was round and we all agreed on that, when I knew that the world was flat and if I went to the edge I would fall off. That night on the train was frightening. Every time I tried to sleep, just as it seemed that I had finally done so, I would wake up sure that thousands of people on horseback were following me, chasing me, each of them carrying a cutlass to cut me up into small pieces. Of course, I could tell it was the (33) sound of the wheels on the tracks that inspired this nightmare, but a real explanation made no difference to me. Early that morning, Mariah left her own compartment to come and tell me that we were passing through some of those freshly plowed fields she loved so much. She drew up my blind, and when I saw mile after mile of turned-up earth, I said, a cruel tone to my voice, Well, thank God I didn t have to do that. I don t know if she understood what I meant, for in that one statement I meant many different things. When we got to our destination, a man Mariah had known all her life, a man who had always done things for her family, a man who came from Sweden, was waiting for us. His name was Gus, and the way Mariah spoke his name it was as if he belonged to her deeply, like a memory. And, of course, he was a part of her past, her childhood; he was there, apparently, when she took her first steps; she had caught her first fish in a boat with him; they had been in a storm on the lake and their survival was a miracle, and so on. Still, he was a real person, and I thought Mariah should have long separated the person Gus standing in front of her in the present

11 from all the things he had meant to her in the past. I wanted to say to him, Do you not hate the way she says your name, as if she owns you? But then I thought about it and could see that a person coming from Sweden was a person altogether different from a person like me. We drove through miles and miles of countryside, miles and miles of nothing. I was glad not to live in a place like this. The land did not say, Welcome. So glad you could come. It was more, I dare you to stay here. At last we came to a small town. As we drove through it, Mariah became excited; her voice grew low, as if what she was saying only she needed to hear. She would exclaim with happiness or sadness, depending, as things passed before her. In the half a year or so since she had last been there, some things had changed, some things had newly arrived, and some things had vanished completely. As she passed through this town, she seemed to forget she was the wife of Lewis and the mother of four girl children. We left the small town and a silence fell on everybody, and in my own case I felt a kind of despair. I felt sorry for Mariah; I knew what she must have gone through, seeing her past go swiftly by in front of her. What an awful thing that is, as if the ground on which (35) you are standing is being slowly pulled out from under your feet and beneath is nothing, a hole through which you fall forever. The house in which Mariah had grown up was beautiful, I could immediately see that. It was large, sprawled out, as if rooms had been added onto it when needed, but added on all in the same style. It was modeled on the farmhouse that Mariah s grandfather grew up in, somewhere in Scandinavia. It had a nice veranda in front, a perfect place from which to watch rain fall. The whole house was painted a soothing yellow with white trim, which from afar looked warm and inviting. From my room I could see the lake. I had read of this lake in geography books, had read of its origins and its history, and now to see it up close was odd, for it looked so ordinary, gray, dirty, unfriendly, not a body of water to make up a song about. Mariah came in, and seeing me studying the water she flung her arms around me and said, Isn t it great? But I wasn t thinking that at all. I slept peacefully, without any troubling dreams to haunt me; it must have been that knowing there was a body of water outside my window, even though it was not the big blue sea I was used to, brought me some comfort. Mariah wanted all of us, the children and me.

12 ( 3 / ) to see things the way she did. She wanted us to enjoy the house, all its nooks and crannies, all its sweet smells, all its charms, just the way she had done as a child. The children were happy to see things her way. They would have had to be four small versions of myself not to fall at her feet in adoration. But I already had a mother who loved me, and I had come to see her love as a burden and had come to view with horror the sense of self-satisfaction it gave my mother to hear other people comment on her great love for me. I had come to feel that my mother s love for me was designed solely to make me into an echo of her; and I didn't know why, but I felt that I would rather be dead than become just an echo of someone. That was not a figure of speech. Those thoughts would have come as a complete surprise to my mother, for in her life she had found that her ways were the best ways to have, and she would have been mystified as to how someone who came from inside her would want to be anyone different from her. I did not have an answer to this myself. But there it was. Thoughts like these had brought me to be sitting on the edge of a Great Lake with a woman who wanted to show me her world and hoped that I would like it, too. Sometimes there is no escape. but often the effort of trying will do quite nicely for a while. I was sitting on the veranda one day with these thoughts when I saw Mariah come up the path, holding in her hands six grayish-blackish fish. She said, Taa-daah! Trout! and made a big sweep with her hands, holding the fish up in the light, so that rainbowlike colors shone on their scales. She sang out, I will make you fishers of men, and danced around me. After she stopped, she said, Aren t they beautiful? Gus and I went out in my old boat my very, very old boat and we caught them. My fish. This is supper. Let s go feed the minions. It s possible that what she really said was millions, not minions. Certainly she said it in jest. But as we were cooking the fish, I was thinking about it. Minions. A word like that would haunt someone like me; the place where I came from was a dominion of someplace else. I became so taken with the word dominion that I told Mariah this story; When I was about five years old or so, I had read to me for the first time the story of Jesus Christ feeding the multitudes with seven loaves and a few fishes. After my mother had finished reading this to me, I said to her, But how did Jesus serve the fish?

13 boiled or fried? This made my mother look at me in amazement and shake her head. She then told everybody she met what I had said, and they would shake their heads and say, What a child! It wasn t really such an unusual question. In the place where I grew up, many people earned their living by being fishermen. Often, after a fisherman came in from sea and had distributed most of his fish to people with whom he had such an arrangement, he might save some of them, clean and season them, and build a fire, and he and his wife would fry them at the seashore and put them up for sale., It was quite a nice thing to sit on the sand under a tree, seeking refuge from the hot sun, and eat a perfectly fried fish as you took in the view of the beautiful blue sea, former home of the thing you were eating. When I had inquired about the way the fish were served with the loaves, to myself I had thought. Not only would the multitudes be pleased to have something to eat, not only would they marvel at the miracle of turning so little into so much, but they might go on to pass a judgment on the way the food tasted. I know it would have mattered to me. In our house, we all preferred boiled fish. It was a pity that the people who recorded their life with Christ never (39) mentioned this small detail, a detail that would have meant a lot to me. When I finished telling Mariah this, she looked at me, and her blue eyes (which I would have found beautiful even if I hadn t read millions of books in which blue eyes were always accompanied by the word beautiful ) grew dim as she slowly closed the lids over them, then bright again as she opened them wide and then wider. A silence fell between us; it was a deep silence, but not too thick and not too black. Through it we could hear the clink of the cooking utensils as we cooked the fish Mariah s way, under flames in the oven, a way I did not like. And we could hear the children in the distance screaming in pain or pleasure, I could not tell. Mariah and I were saying good night to each other the way we always did, with a hug and a kiss, but this time we did it as if we both wished we hadn t gotten such a custom started. She was almost out of the room when she turned and said, I was looking forward to telling you that I have Indian blood, that the reason I m so good at catching fish and hunting birds and roasting corn and doing all sorts of things

14 L U (J Y is that I have Indian blood. But now, 1 don t know why, I feel I shouldn t tell you that. I feel you will take it the wrong way. This really surprised me. What way should I take this? Wrong way? Right way? What could she mean? To look at her, there was nothing remotely like an Indian about her. Why claim a thing like that? I myself had Indian blood in me. My grandmother is a Carib Indian. That makes me one- quarter Carib Indian. But I don t go around saying that I have some Indian blood in me. The Carib Indians were good sailors, but I don t like to be on the sea; I only like to look at it. To me my grandmother is my grandmother, not an Indian. My grandmother is alive; the Indians she came from are all dead. If someone could get away with it, I am sure they would put my grandmother in a museum, as an example of something now extinct in nature, one of a handful still alive. In fact, one of the museums to which Mariah had taken me devoted a whole section to people, all dead, who were more or less related to my grandmother. Mariah says, I have Indian blood in me, and underneath everything I could swear she says it as if she were announcing her possession of a trophy. (41) How do you get to be the sort of victor who can claim to be the vanquished also? I now heard Mariah say, Well, and she let out a long breath, full of sadness, resignation, even dread. I looked at her; her face was miserable, tormented, ill-looking. She looked at me in a pleading way, as if asking for relief, and I looked back, my face and my eyes hard; no matter what, I would not give it. I said, All along I have been wondering how you got to be the way you are. Just how it was that you got to be the way you are. Even now she couldn t let go, and she reached out, her arms open wide, to give me one of her great hugs. But I stepped out of its path quickly, and she was left holding nothing. I said it again. I said, How do you get to be that way? The anguish on her face almost broke my heart, but I would not bend. It was hollow, my triumph, I could feel that, but I held on to it just the same.

-

-

-